Critical Conversations: Navjot Kaur on Sikh Representation in Children's Books

Illustration by Gurleen Rai from Dreams of Hope by Navjot Kaur

Navjot Kaur is an author, educator, and founder of Saffron Press, an independent publisher representing the Sikh identity in children's books. Kaur sat down with us to discuss the state of Sikh representation in children’s books and her experiences advocating for accurate information and narratives about the Sikh identity.

Our conversation with her is transcribed from a 40 minute interview. The questions and responses are numbered for easy navigation through the text. This is a chronological list of the topics discussed:

Kaur's background in education and why she started Saffron Press

Kaur’s advocacy and activism around misrepresentations of the Sikh identity and Sikh dastaar in children’s books, including the recently released “multi-faith” book, Hats of Faith

The meaning and significance of the Sikh dastaar (turban) and why it's not a hat

Institutionalized oppression within children's publishing. The experience of being gaslighted, disregarded, and silenced by authors, illustrators, and publishers when speaking up about inaccurate representations of the Sikh identity.

What it means for authors and/or publishers to use one person as a representative from a community to justify a narrative that other members of the community say is harmful.

The state of Sikh representation in children's books and who is dominating the narrative.

Should institutions and/or organizations track statistics about books published by and about members of religious communities? For example, the Cooperative Children's Book Center tracks annual statistics on children's books being published by and about BIPOC.

How citizens, educators, and consumers can critically support advocacy for the Sikh community in both literature and everyday interactions

Children’s books that positively and accurately represent the Sikh identity. The books Saffron Press has published and where people can find them.

1. The Conscious Kid (TCK): Can you tell us about your background in education and why you started Saffron Press?

Navjot Kaur (NK): I was a classroom teacher for over a decade and taught in England and Canada amongst varied community demographics. Through these opportunities I was able to experience diverse perspectives and voices over the years, whether they were socio-economic, or racial. When you are the only teacher of colour in a school, that too brings its own distinct experience.

I was always very aware and cognizant of the books I was sharing with my students, whose voices were being heard, and whose were not being amplified at all. When I began thinking about the First Nations people of Canada, considering Indigenous voices, and how their history is reflected and represented in the textbooks that we used in school, a more critical dialogue emerged in the classroom. We really questioned how the First Nations people were being represented, reflecting on the history behind the term “Indian”, and how their history was being told. I immediately connected to the pain associated with assimilation and long hair being cut away from children taken to residential schools. We were already disrupting texts in our classroom without even realizing it. I was on my way to creating a more inclusive and equitable learning environment as a social justice teacher.

As I went along this journey, I became a mom. We learned that our son was Deaf with a profound hearing loss and that he would be wearing hearing aids. The Deaf community became another community I knew nothing about. Even as a teacher, I had never experienced a child with hearing loss in my class. This really brought attention to the way I considered the term diversity and my own investment in becoming more informed about the world. Up until that point, I was really looking through an ethno-racial lens, more focused on race/ethnicity and religion. Now, life had forced me to reflect on diversity way beyond that point.

I started thinking deeper about the books I was sharing with my son. He would always bring a whole pile of picture books and board books and throw them on the bed to read together. Even though I tried to source diverse books, there were very few books that included a character who reflected the Sikh identity. This experience made me pause and consider what I would spend my time doing while I was a stay at home mom. With my love for literature, especially children’s books, it seemed second nature that I would polish the writing I had worked on for a decade before and try to submit these manuscripts to traditional publishers. I received so many rejections at the time, some because the Sikh identity was not well understood. People in the industry assumed that the Sikh community would be the only readers interested in the stories, and the community, apparently, were not book buyers.

With my teaching background, and becoming a mother to a child with hearing loss, I knew that our son would need a very strong foundation to go through life with his visible Deaf identity, along with his equally visible faith identity. I wanted him to have that representation available as an accessible resource before he started school and so I launched Saffron Press, an independent publisher representing the Sikh identity in children's books.

Illustration by Gurleen Rai from Dreams of Hope by Navjot Kaur

2. TCK: You are a strong advocate for accurate representations of the Sikh identity in children's literature. The “multi-faith” board book, Hats of Faith that was released last year in the UK and is now being published and distributed in the US, misrepresents the Sikh identity and the Sikh dastaar. Can you speak about your advocacy and activism around this book?

“We have a responsibility as publishers, as authors, as illustrators, as artists, to ensure that the images, and content we share, is accurate and aligned with our values around diversity, equity and inclusion. It’s not about meeting the trend of diverse books. ”

NK: I should share some context here. When I refer to dastaar, I am referencing a turban worn by people of Sikh identity. A turban itself can be worn by people from many cultures around the world and its significance would be different for each culture.

My advocacy stems from experiences of oppression. These experiences can differ widely for those identifying as a Sikh person. If you identify as a member of the Sikh community, there are intersecting identities which can form very diverse narratives. I use my background, voice, and perspective to advocate fiercely for accurate representation of the Sikh identity in children’s books.

When considering conscious or unconscious bias, we know that it can stop equitable opportunities for people to succeed. We have to think about and question bias because those biases get reflected in children’s books. Children as early as 2 years old begin following their schema about who they’re going to like and who they’re not going to like, based on the way people look or have been perceived. We have a responsibility as publishers, as authors, as illustrators, as artists, to ensure that the images, and content we share, is accurate and aligned with our values around diversity, equity and inclusion. It’s not about meeting the trend of diverse books. Advocates for diversity understand the power of words and our collective responsibility to ensure that these words are accurate and respectful of diverse communities. The title of a book then, is as important as its content.

“We have to think about and question bias because those biases get reflected in children’s books. ”

I was immediately drawn to the Hats of Faith book because the illustrations were so colorful and inviting. It was wonderful to see the Sikh identity represented right on the front cover and a Patka on the back cover. But within seconds, I saw the title and my heart sank. Reading the title took the anticipation of something beautiful away and I thought, did they even do their work? Did they dismiss the voice of the Sikh community? Because the dastaar is definitely not a hat.

Given the nuances of a Sikh person growing up in England, I appreciate why some people in our community have learned to be non-confrontational in the face of power. When you’ve experienced being chased home by skinheads, fearing for your life as a child, you learn that it’s safer to be invisible, to be silent. When you’ve been taunted and bullied because of your visible faith identity, it pulls you down. That trauma stays with you. Decolonizing your mind takes time—and by decolonizing I’m referring to the process of changing the way we view the world. We don’t have to be eternally grateful every time we get a mention by people outside of our lived experiences. When the Sikh identity is given space, and it’s inaccurate, we have to raise our collective voices to change who holds power over our stories.

“I’m still taken aback when the voice of a person living the Sikh experience is dismissed. Marginalized voices do not have to accept inaccuracies and misrepresentations. Not listening to and not considering us becomes another form of oppression. When we’re faced with people who may have more power than we do, it becomes really difficult to make them understand that our narratives exist—and we deserve for them to be accurate.”

I’m still taken aback when the voice of a person living the Sikh experience is dismissed. Marginalized voices do not have to accept inaccuracies and misrepresentations. Not listening to and not considering us becomes another form of oppression. When we’re faced with people who may have more power than we do, it becomes really difficult to make them understand that our narratives exist—and we deserve for them to be accurate.

3. TCK: Can you give us a brief understanding of the dastaar and its significance? Can you elaborate on why it's not a hat?

NK: Not all people who identify with the Sikh faith wear a dastaar. Sikhism is a journey. Sikh means to be willing to learn something new, someone who is on a journey of learning throughout their life. The Sikh dastaar is defined as an article of faith. A female dastaar-wearing friend once shared with me that it is better understood as a daily action of faith, which I found empowering. It can be worn by any gender. In Sikhism, women were given equal rights over 300 years ago in a society that considered them property. Cultural traditions have intersected Sikh faith identity in such a way in some parts of the world that the root values have been diluted with socio-cultural values.

When I think of the Sikh dastaar as a daily action of faith, I see how my son watches intently as his father, his uncle or his grandfather tie their dastaar every morning. He is in awe of its possibility. He has questions about how and why and when he too will be able to tie one. Simply, the dastaar covers the long hair that we keep as Sikhs. It is a daily action of faith in the sense that it’s almost a form of meditation to help still the mind and bring your day into focus. It reminds the person wearing it, that their choices and words need to be aligned with the actions of their Sikh faith. The daily action of tying a dastaar becomes a journey to uplift your mind, and a reminder to never leave any one community on the outside. I think when children grow up learning to tie the dastaar, and learning about the meaning behind it, they’re also grasping what it means to become citizens of change. It takes courage, a growth mindset and lots of determination to do the right thing.

Illustration by Gurleen Rai from Dreams of Hope by Navjot Kaur

Hopefully this dispels any myths about the Sikh dastaar and clarifies why it cannot ever be considered an accessory, like a hat.

4. TCK: Yes, absolutely, thank you. Related to what you were talking about with your interaction with the initial publisher, I want to go back to that, because it wasn’t just the initial publisher that was not receptive to your feedback, it was the author, illustrator, other publishers, etc. so can you speak a little bit about the experience of your voice not being listened to or regarded on a wide, almost systemic level in publishing and the kid lit community?

NK: It was difficult for me to raise my voice around this issue at first. I was exposing myself to a lot of vulnerability at the time. You have the possibility of being attacked and having to face those microaggressions, that, as a person of color, you face so often. I am a small publisher myself. I’ve had to work fearlessly to ensure that the advocacy work I do values marginalized voices. If there’s something I could do better, I take the time to go out and learn about it because I want to be informed and can always do better. During the time that this book gained traction, nobody else was speaking out and it seemed to fit the narrative of so many people looking for diverse books, which was scary. And that’s when I reached out to friends - Sikh scholars, Sikh organizations, people within the Sikh community and asked for their insight.

When my son was in kindergarten, his patka (small dastaar) was pulled off his head by the child sitting behind him. Children are curious, I know, and they have questions, and that’s fine. I absolutely encourage children to ask questions. You can’t disregard incidents like this though, as if they’ll never happen again. You have to wonder, what could we have done better? What kinds of books could be on the classroom shelves? What conversations should we be having with the young people in our lives?

“When my son was in kindergarten, his patka (small dastaar) was pulled off his head by the child sitting behind him. You can’t disregard incidents like this as if they’ll never happen again. You have to wonder, what could we have done better? What kinds of books could be on the classroom shelves? What conversations should we be having with the young people in our lives? ”

The advocacy around diverse books is tiring, and often it’s lonely work, as you know.

If I was to be silent at this time, I would be giving up on my values. When sharing our truth, we have to be willing to expose ourselves to all kinds of vulnerabilities. I challenged the term “hat”, and was told that I wasn’t “cultivating kindness” when questioning a (white) person marketing a diverse book. Trying to silence a marginalized voice is a form of oppression, so you will not dare speak up again. When offering feedback to a publisher, author or illustrator who may have made a mistake (because we all make mistakes), all you’re asking for them to do is consider a different perspective. It’s harder to achieve when the work is done. Taking the issue of a problematic title seriously before selling world rights could have been an act done in good faith.

My pre-teen son had questions for me as he slipped in and out of watching me type responses to the kidlit community. Within ten minutes, he had come up with two alternate titles for the book, which would respect the head coverings of all the faiths represented in the book. Ten minutes.

There is a need for accurately represented diverse identities in children’s books. But if you discard the very voices you say you want to amplify, then that is reinforcing oppression.

“There is a need for accurately represented diverse identities in children’s books. But if you discard the very voices you say you want to amplify, then that is reinforcing oppression.”

TCK: To clarify, no Sikhs were involved in the creation of the book, the author and the illustrator are both white?

NK: The author, I believe, is Jewish and the publisher, I believe, is a Muslim woman. From their website, it reads that they did consult people from all of the faiths represented in the book. I did ask if they would be willing to share who offered the Sikh perspective, but there was no transparency in who was actually involved in the decision to approve the title Hats of Faith.

5. TCK: Right, and I think that’s something we see happening a lot. People see or pull in one person as a representative from a community and they will use that one person or opinion to justify the narrative, even when that narrative is harmful to that very same community or group.

“When problematic books continue to be distributed even after people with lived experience have raised their voices, advocacy work will not weaken, it will only gain strength. We will realize that there is much work still to be done for accurate representation and we will do it.”

NK: Absolutely and like I said, I use my voice and experience, but there are layers of nuances within the Sikh community, depending on your cultural environment. A person’s cultural experiences as a Sikh growing up in the United Kingdom where this book was first published, versus living in North America, will be very different, even though they follow the same faith belief. Asking a token person for their perspective while writing a book like this is not enough. Before buying the rights of a book like this around the world, representatives should ask questions and have cultural sensitivity readers share insights. When problematic books continue to be distributed even after people with lived experience have raised their voices, advocacy work will not weaken, it will only gain strength. We will realize that there is much work still to be done for accurate representation and we will do it.

6. TCK: Right, and to put it in context, there’s just not that many children’s books about Sikhs out there. Can you talk a little bit about the state of Sikh representation in children's books? How common is it? Who is writing and dominating the narratives?

NK: You’ve done your work! The search can be futile, with very few books that include the Sikh narrative in traditionally published children’s literature. Self-publishing or independent avenues are changing the landscape though. In the schools I attended in England, we saw our mirrors revealed during multicultural days and books about faith, the foods we eat, and the festivals we celebrate. But even those were not always reflective of my life as a south-Asian child growing up in England because the books were usually set in India. The nuances of a child growing up in India are very different from the nuances of a child growing up in England, the US, or Canada.

Publishers may create these books thinking they have represented specific populations, but that’s a very, very narrow perspective. When you look at the books that are available today in Canada, there’s not a huge change as far as content, but what is different is the appetite for culturally relevant children’s books for people of Sikh (or culturally diverse) heritage raising little ones. I’ve experienced how mindsets have shifted over the years. They are yearning for high quality children’s books that move away from stereotypical narratives. I feel like the generation rising up now is more invested in the Arts and we’re seeing some amazing illustrators, actors, writers and spoken word artists from the [Sikh] community. Hopefully they will be the poets and storytellers who create representation in the books children see in the future. Currently, there are books that are representing the Sikh identity within illustration spreads (which is amazing!) but many still are focused on faith-based narratives, or are novels or Poetry books (Rupi Kaur!) for an older age range.

7. TCK: The Cooperative Children's Book Center tracks statistics on children's books by and about people of color—they break it down annually by race. Is there anyone who tracks statistics like this for religion?

NK: I don’t believe there is anybody who creates statistics around children’s books when it comes to religion, but the Sikh Coalition in the US has been gathering data and statistics around the bullying of Sikh children in schools. They found 67% of Sikh children report being bullied at school which is at a rate two times higher than the national average. A few years ago after my son encountered an incident of bullying, I was told that this specific data is not collected in Canada. If familiar with the words of Rudine Sims Bishop, you will have heard about the need for books to act as mirrors, windows and sliding glass doors. Books that do this can affirm a child’s self-identity and encourage belonging. These stories help scaffold difficult conversations and open windows into worlds that less diverse populations may otherwise never encounter. Data drives change and awareness around such studies and statistics can push the conversation forward.

“The Sikh Coalition in the US has been gathering data and statistics around the bullying of Sikh children in schools. They found 67% of Sikh children report being bullied at school which is at a rate two times higher than the national average.”

8. TCK: How can citizens, educators, and consumers critically support advocacy for the Sikh community in both literature and everyday interactions?

NK: By buying books or supporting our work through your voices.

CNN recently aired a United Shades of America episode featuring Sikh Americans with W. Kamau Bell leading the conversation. It was groundbreaking in the sense that it was the first time an hour-long cable episode had been dedicated to sharing the Sikh narrative. I think it was eye-opening because as Sikhs, we don’t often see ourselves represented across media in a positive light. That was one of the few times that voices from the Sikh community were actually heard and shared through a major network. When I read the comment section after the episode aired, it was so interesting to read how little was known about us. On the one hand I was thinking, it’s taken us having to do the education again to achieve this. But just like Heritage Months, it was necessary work. People came forward to share the hate and discrimination faced by the Sikh community over the last several years (especially after 9/11) as something that needs to change. The 6-year anniversary of the Oak Creek shooting in Wisconsin, killing members of a Sikh congregation just passed on August 5th. In the last few days, two elderly Sikh men have been brutally attacked in central California.

In Canada, even though there was a demonstration planned to take place in Toronto over the weekend by Canadians Against Islam, (it did not go ahead), there has been no urgency to propel conversations around the lack of diverse representation in children’s books. Books acting as mirrors, windows and sliding glass doors are needed now, more than ever. Instead, there remains a quiet complacency to trust the reputation of Canadians as polite, open-minded citizens, who would not possibly act in the way of our neighbours to the south. Every time our family has experienced micro-aggressions, what haunts me is the silence of bystanders.

“Every time our family has experienced micro-aggressions, what haunts me is the silence of bystanders.”

One of the largest populations of Sikh people in Canada, live in Surrey, BC. From the 2011-2016 Census data, I found that 21% of Surrey’s population identified Panjabi as their Mother tongue language. After almost 7 years of living in the province and experiencing the public school system, I can confirm that I never came across a single children’s book representing a main character from the Sikh community in any of my son’s classrooms. Not once. I either had to offer free presentations/author visits or gifted my books to each classroom in order to ensure culturally responsive representation. The books rarely made their way out of the closet the rest of the year. This is what we see as parents of colour, as Sikh parents, when our children enter classrooms. We feel their fear. We feel their pain when they are not understood. We do the work, we need you to walk with us.

“I never came across a single children’s book representing a main character from the Sikh community in any of my son’s classrooms. Not once.”

TCK: There is so much misunderstanding. I know in the US, many people seem to lump Sikhs and Muslims into the same category and don’t see or understand Sikhs as a distinct, separate identity, culture and religion. A lot of times, Sikhs in the US are targeted for hate crimes because the dastaar gets associated with Islam. There’s just so much lack of awareness out there—on both Sikhism and Islam—and definitely in children’s books and in the classroom like you said.

“We need to question and challenge all representations when they’re inaccurate because otherwise we’re just propelling the same stereotypes and giving power to the people who have oppressed marginalized communities over the years.”

NK: We need to question and challenge all representations when they’re inaccurate because otherwise we’re just propelling the same stereotypes and giving power to the people who have oppressed marginalized communities over the years. Whether a person identifies as a Sikh or a Muslim, we cannot trample upon any one community in our race forward to bring awareness to our own narratives. I think it comes back to the fact that if the Sikh community remains silent and accepts any representation, whether it’s accurate or not, nothing will change. Instead, it becomes problematic. We cannot rely on PR campaigns, or public Turban Tying events (which I have issue with) to educate the ignorance that leads to hate. It begins with each one of us speaking up when we see or hear something wrong. The work of education cannot fall on the shoulders of any one community. It’s truly important as a society that we invest in diverse voices and accurate narratives in children’s literature. This is the work of advocacy even when it looks or sounds harsh. It may not be easy, but it will be worth our time. At the end of The Garden of Peace, I mention the Sikh Ardaas - my son has always called it his wish for today - it ends with our purpose for the day, referred to as Sarbat da Bhalla - may we strive for global prosperity.

9. TCK: You do an incredibly meaningful and beautiful job creating children’s books representing the Sikh identity. Do you want to speak to the books that you’ve published, and where people can find them?

NK: Thank you, I really appreciate your kind words. As a small publisher, it’s only with the advocacy and support of organizations like The Conscious Kid that I’m able to get my voice heard. Books that raise critical dialogue and encourage little readers to think about how they too can become citizens of change are available on the Saffron Press website. Saffron Press books are printed on responsibly-sourced paper, so we can help keep forests healthy for future warriors of change. A portion of our sales helps to provide prescription eyeglasses to the over one million children of the world with treatable loss of sight.

In A Lion’s Mane, A young boy goes on a quest to explore the meaning of the Sikh dastaar, which covers his lion's mane. On this journey he learns what the lion means to cultures around the world and relates these values back to his own identity. He comes across the Teachings of the Seven Grandfathers from the Anishinaabe-Ojibwe nation, the embroidered lion rugs of Iran, and joins in a vibrant Chinese lion dance on his travels.

Dreams of Hope gives every little one a place to imagine reaching for dreams. Whilst her Father sings an ode to the beauty of the natural world, Little One imagines the world beyond her immediate window. She hears about endangered Chirus high in the Tibetan mountains, and blue whales singing their very own lullabies deep in our oceans. It gives little ones a moment to think about what beauty really means for them and to reflect on our responsibility to care for the diversity of this planet.

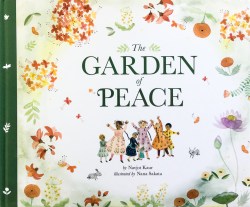

The Garden of Peace is an allegory rooted in the social despair of a time not too contrary to our own. The Garden of Peace uses the metaphor of weeds to introduce the difficult concept of social inequity and allows readers to think and talk about big ideas like discrimination. Although inspired by the 300 year-old story of Vaisakhi, readers will discover a new perspective of how a nation building event in Sikh history, harvested citizens of change. With simple steps on how to grow your own garden of peace in the back.

TCK: Is there anything else that you wanted to say?

NK: I’d like to thank you for considering Saffron Press for your Critical Conversations because it truly places value on the work that small presses and independent authors are doing. Without platforms like these, we cannot amplify the need for diverse voices and accurate representation in children’s books.

Although I’ve had to minimize time spent on social media, I cannot say enough about the amazing supporters I’ve found through Instagram, school visits and summer camps. The hard-working small, local businesses and museum shops who choose to stock Saffron Press titles are superstars. Supporters of Saffron Press have been my life line during some uncertain moments. I see you and send my warmest gratitude.

TCK: We are so grateful for your work, your voice, and your continued advocacy. We are honored and grateful for the opportunity to support the work you’re doing.

You can find the Saffron Press website here: https://saffronpress.com/

Links to the books Saffron Press has published can be found here:

Saffron Press can be found on Instagram here: https://www.instagram.com/saffronpress/